Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

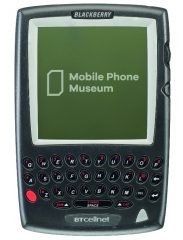

BlackBerry has been a staple in many people’s lives across the globe for the past couple of decades, so it has saddened many that the iconic smartphone brand has officially waved goodbye to its classic devices.

This comes after the vendor announced in 2016 that it would be transitioning from a device to a software company, moving its focus away from making phones.

Sealing this transition five years later, BlackBerry said it would stop running the phone’s legacy software from January 4.

Announcing the move in a statement, the vendor said: “As of this date, devices running these legacy services and software through either carrier or WiFi connections will no longer reliably function, including for data, phone calls, SMS and 9-1-1 functionality.”

Newer devices running on Android software will still work, but we officially part ways with the BlackBerry Messenger (BBM) service that made the brand so popular.

Earning the nickname ‘crackberry’ for how addictive they were, they appealed to the masses and were used by teens, office workers and celebrities – while even Barack Obama owned one during his presidency.

In a bizarre move, Alicia Keys was appointed global creative director in 2013, but left after one year following a disastrous financial year for the company.

Before the celebrity endorsements and financial woes, BlackBerry was king of the smartphone for several years, sustaining huge market share well into 2011.

It sold more than 50 million units per year at the height of its success around 2009 to 2010 and controlled 20 per cent of the global smartphone market.

BlackBerry’s user base hit 21 million users in the US and 36 million worldwide in the fourth quarter of 2010.

Just nine million remained in the US by the end of that year. At the same time, BlackBerry’s global market share plummeted from 20 per cent in 2009 to less than five per cent in 2012.

Things then got even worse, with BlackBerry’s market share continuing to tumble and reaching close to zero per cent in 2016.

So why did the company start to see a decline in customers so soon after its success?

The answer lies in the guise of Steve Jobs and the groundbreaking invention of the iPhone, the first version of which arrived in 2007.

The iPhone was innovative and provided customers with a full touchscreen device that they had never seen before, but BlackBerry believed its physical keyboard would still reign supreme.

CCS Insight chief analyst Ben Wood believes that BlackBerry was not prepared for the changing smartphone market and couldn’t keep up with the evolving phone generations that Apple delivered every year.

“BlackBerry completely underestimated the impact of the iPhone,” he says. “It felt that the lack of a QWERTY keyboard would make the iPhone an inferior device for text input.

“It also misjudged how quickly Apple would embrace business-centric capabilities such as decent email and beefed up security.”

CEOs Mike Lazaridis and Jim Balsillie publicly berated the iPhone, its short battery life and weaker security, but this gave the men a reputation for being arrogant.

Apple began to steal BlackBerry’s business customers and once the iPhone 4 was released in 2010, it cemented the rapid decline of BlackBerry as Apple soared ahead in sales.

When the vendor finally accepted that the iPhone was here to stay, the company rushed to deliver more of a touchscreen experience.

“When the company finally announced its new BlackBerry 10 operating system [launched in 2013], which made it possible to deliver full touchscreen devices, it was too little too late,” says Wood.

“The final nail in the coffin was likely the massive outage in 2011 when it lost service for three days. People lost faith in the platform and were prepared to look at other devices.”

With the Android operating system also on the rise by that stage, having launched in 2008, it created an additional confounding factor for BlackBerry.

IDC senior research manager Marta Pinto agrees that it was too late for BlackBerry to stay strong in an ever-evolving market and that change was needed.

“Staying competitive was going to be a tough job,” she says. “More vendors coming to the market, the early success of Apple in some of the most expensive geographies and the standardisation of Android on the other hand, meant that BlackBerry would have to innovate either on hardware or create an alternative proposition to iOS or Android.

“There were other options, such as to try and completely revamp the hardware, but BlackBerry was already slow to launch devices at a moment in the market where devices were being launched every week. The competition was fearless.”

Wood thinks that several company decisions contributed to its issues. “Early signs of how conservative BlackBerry was about adopting new technologies came when the company was slow embracing new capabilities such as colour screens and cameras,” he says.

“There were valid reasons for this, such as for maintaining good battery life and BlackBerry’s perception as a secure device – but it felt like the company missed the fact that its customers, who were mostly business people, were also consumers when they were not at work.”

BlackBerry continued to focus on its business customers, concentrating on aspects including security, connectivity and updating existing features, whereas Apple and Samsung were constantly innovating and making smartphones accessible to a variety of consumers.

These brands ramped up their third- party app ecosystems, whereas BlackBerry was stubborn in keeping to its own first-party development before turning to Android in the mid-2010s when it was, yet again, probably too late.

“BlackBerry needed to pivot more quickly away from its traditional hardware and operating system,” says Wood. “With the benefit of hindsight, a faster transition to Android might have been a smart move, but that was far from clear at the time.”

Pinto adds: “The consolidation in two operating systems aggravated the situation for BlackBerry, as the appeal of a managed ecosystem of apps exclusive to secure BlackBerry devices was lost.”

Both analysts say the situation worsened when BlackBerry was also slow to adapt from 3G to 4G.

Wood says the team didn’t feel the need to rapidly transition and focused on marketing its 3G devices, while Pinto says delaying the shift to 4G meant BlackBerry didn’t have a competitive advantage.

“In a full 3G world, having a keyboard and BBM was a cutting-edge thing,” she says.

“But in a 4G era, apps and the ability to perform more on the screen meant the iconic BlackBerry form was no longer suitable.”

The vendor’s tribulations continued throughout the 2010s, as it reported losses in nearly every quarter and a huge volume of its Z10 devices were left unsold months after they hit the market in January 2013.

This led to 40 per cent of the workforce being cut, meaning 4,500 jobs globally were lost under CEO Thorsten Heins.

Heins had replaced long-term CEOs Lazaridis and Balsillie, who stepped down in early 2012 in a bid to save the company.

Before leaving, Balsillie wanted to push wireless carriers to take on BBM as a replacement for SMS, regardless of what phone the consumer used.

BBM had no extra cost, unlike with text messages, while it provided enhanced privacy because users received a PIN instead of a mobile number or email.

This idea was rejected as soon as Heins took over, causing Balsillie to cut ties with BlackBerry entirely.

Instead of trying to overhaul the company, only small changes were made, such as fixing existing features – with BlackBerry seemingly not learning the lessons of the past.

But Heins nevertheless remained bullish for the future, predicting in one interview that by 2018 BlackBerry would be the leader in mobile computing – a forecast that turned out to be far wide of the mark.

“40 or 50 per cent of all mobile workers will use this one single device as their mobile computing programme,” he said.

“There is no more laptop; I doubt whether there will be a laptop in a few years from now or a tablet because you can just connect it to a big screen and off you go.”

As we know, this didn’t happen and we now have more devices than ever. Few of these are BlackBerries, with the brand licensed by TCL in 2016 after its market share effectively slipped to zero per cent.

Analysts suggest that the company could have done more to save itself. “BlackBerry was able to secure a good brand equity and could have leveraged that in many ways,” says Pinto. “Having a vision of future corporate needs in a 4G world would have been a great opportunity, as back then there was no Android Enterprise Recommended programme.

“BlackBerry could have spotted – and secured, early on – a footprint in B2B as a preferred secure Android vendor, for example.”

Current CEO John Chen knew that BlackBerry couldn’t work in the smartphone market, transformed the brand into a successful cybersecurity software firm.

When announcing the decommissioning of BlackBerry services, Chen spoke of how the company had “invested and invented” its way to taking leadership positions in cybersecurity.

In 2021, BlackBerry prevented more than 165 million cyberattacks and has developed security services such as encrypted voice and digital communications, as well as automotive safety.

Wood thinks that Chen’s overhaul of the brand and shift to software and security was its only option, and Pinto agrees as other companies such as LG have also seen success after withdrawing devices from the market to focus on other profitable segments.

With OnwardMobility acquiring the licence for Blackberry in 2020 after TCL dropped it, will we see a comeback for the company in the smartphone market?

“Let’s see… the final roll of the dice will come with OnwardMobility,”

says Wood. “It has promised to deliver a BlackBerry device in 2022 and there are still some diehard BlackBerry enthusiasts out there, but it is certainly a niche opportunity.”

After experiencing delays and shipping issues in 2021, OnwardMobility CEO Peter Franklin said the brand will start to deliver some “next- generation 5G devices”.

The company announced that it will provide customers with a secure 5G smartphone and, undeterred by historical events, still equipped with a keyboard.

However, Pinto warns that there is a lot to consider for a brand to make a comeback.

“First the timing might not be right,” she says. “With all the volatility in the market and struggles in the supply chain and with transportation, a comeback would be 10 times harder.

“Also the competitive landscape today is very different from 10 years ago, and BlackBerry would have to relearn the market and adapt to new trends way faster.

“Apple, Samsung, Xiaomi and others have also gained another advantage: they have an ecosystem of devices that BlackBerry doesn’t have, and the vendor therefore has less opportunities to show consumers the advantage of rebuying a BlackBerry phone.”